Equine Extension Program

Internal Parasites

Background

All members of the horse family are subject to internal parasitic infection. From the practical standpoint the most important internal parasites are strongyles, ascarids, pinworms and bots. The digestive tract, or stomach and intestines, is the most commonly affected area, along with migration through other tissues and organs such as heart, liver, lungs, and blood vessels.

A general knowledge and understanding of the nature of these parasites and their development is essential before necessary prevention and control measures can be effectively applied.

Strongyles are the most injurious, whereas ascarids, bots and pinworms generally are less harmful. A few parasites may be tolerated by the horse without apparent signs of ill effect but large numbers are quite apt to be harmful.

Horses affected the most by parasites are young sucklings or weanlings and yearlings. Generally speaking, ascarids and pinworm infection are probably restricted to young horses. This is because resistance or immunity is built up by the time a horse is 2 or 3 years old, in most cases. Strongyles and bots however effect horses of all ages.

Strongyles

The strongyles, or blood sucking worms, feed on blood from the host animal. They are

found in the intestines where they cause extensive damage to the blood vessels and

the mucous membrane. The loss of blood results in anemia and makes the animal. more

susceptible to bacterial infections.

The strongyles, or blood sucking worms, feed on blood from the host animal. They are

found in the intestines where they cause extensive damage to the blood vessels and

the mucous membrane. The loss of blood results in anemia and makes the animal. more

susceptible to bacterial infections.

How your horse becomes infected: The infective larvae are ingested when the horse grazes on contaminated pastures or eats contaminated feed. The larvae migrate extensively, causing damage to many organs and tissues (particularly to the walls of blood vessels which may develop aneurysm and eventually cause death). The larvae of one species of strongyle may penetrate the walls of arteries particularly, those that supply blood to the intestines, causing recurrent colic. The larvae require 6 to 8 months to reach maturity. The adult parasites then migrate to the large intestine and remain there during their adult life.

Health Effects: The adult worms penetrate the intestinal wall, attach themselves to small blood vessels, and thus secure the blood necessary for them to survive. The injury to the intestinal wall results in interference with the digestion and absorption of food, as well as loss of blood. The adult females lay thousands of eggs daily and these pass out of the body in the manure.

When the temperature is 75 to 800° F, the eggs hatch in approximately 20 hours. The resulting free-living larvae develop into the infective stage in 5-6 days. They are then capable of infecting the horse when ingested and must be ingested to complete the life cycle. Freezing stops the hatching of the eggs and the development of the larvae but does not kill either. Heat generated by composted manure kills both. Larvae live about 3 months on the average but may live for a year or even longer in moist, cool climates.

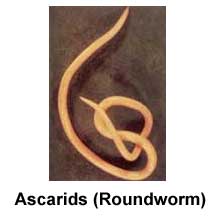

Ascarids

Ascarids or roundworm infections are primarily a problem of young horses. They seldom

cause significant damage in animals that are 11 years or more old. They are primarily

found in the small intestine.

Ascarids or roundworm infections are primarily a problem of young horses. They seldom

cause significant damage in animals that are 11 years or more old. They are primarily

found in the small intestine.

How your horse becomes infected: Infective eggs are taken in with contaminated feed and water. The eggs hatch in the small intestine and the microscopic larvae penetrate the intestinal wall, enter the blood stream, and are carried to the liver and lungs.

Health effects:: Heavy numbers of larvae can cause severe inflammation and destruction in the liver and the lungs. After approximately one week in the lungs the larvae move up the trachea, are coughed up and swallowed again. When they reach the small intestine the second time they quickly mature, become adult worms,

and produce eggs. While ascarids do not attach themselves to the intestinal wall as the strongyles, they do utilize a great deal of food, excrete toxic wastes, depress growth and development, cause digestive disturbances, and produce potbelly.

The eggs pass out in the manure but do not hatch outside the host. They do embryonate and become infective in 10-14 days. The eggs are quite resistant, especially to drying and freezing, and can remain alive and infective for 5 years or longer. Heat is harmful to them and the hot, dry weather of summer or the heat generated in composting can destroy many. Lye is also effective in destroying ascarid eggs.

Bots

Stomach bots are the larvae of the horse bot flies. There are more than one species and they differ primarily in the location on the horse, where the eggs are laid, and in the way in which the eggs hatch.

How your horse becomes infected: During the summer and early fall, eggs are deposited by the bot fly on the hair of the forelegs, shoulders, lips, and muzzle of the horse. The eggs hatch as they are licked by the horse and enter the mouth via the tongue.The minute larvae burrow into the tongue, remain there for approximately one month and then migrate to the stomach.

Health effects: They attach themselves to the mucous membrane living in the stomach, causing damage to the stomach wall and sometimes producing a fatal colic when they block the valve located at the juncture of the stomach and small intestine. The larvae remain in the stomach for 8–10 months until they have completed their development. They detach themselves from the wall and are passed out in the manure.

The larvae pupate outside the host and the mature fly emerges in about one month. The flies mate and reproduce, thus completing the life cycle, The female fly darts at the horse very quickly and repeatedly, attaching an egg to a hair each time. While the flies do not bite, they do annoy the horses, causing them to run or exhibit a restless condition.

Pin Worm

Pin worms are less harmful than the parasites discussed previously. They cause rectal irritations primarily.

How your horse becomes infected: Horses become infected by consuming feed and water contaminated with infective worm eggs.

Health effects: Immature worms can produce severe damage to the mucous membrane in the upper large intestine. The details of the life cycle of these worms are not completely known. It is known that the worm lives in the lower intestine where they produce a moderate inflammation. The females leave the rectum and deposit their eggs on the skin around the anus, causing an intense itching which the horse attempts to relieve by rubbing the tail.

Signs & Symptoms

Symptoms of worm parasitisms may be confused with symptoms of bacterial, viral, or other disease organisms so the use of fecal samples is valuable to aid the veterinarian in diagnosing the presence of worms. Especially in young animals the following symptoms may be observed when many worms are present:

- Unthriftiness. The colt grows slowly or older horses fail to maintain normal weight.

- Rough coat. Hair appears to lie in an abnormal position, is variable in oiliness and seems to "stand up" even with relatively short coats during the summer.

- Anemia. Membranes of the eyes, lips, nostrils, and tongue are a lighter pink than in uninfected horses. Hematocrit (number of red blood cells per unit of blood) values may be below normal and there may be less hemoglobin in blood than normal. Anemia also may be caused by many bacterial or viral organisms as well as nutritional deficiencies.

- Diarrhea. While this condition is highly variable it can be of diagnostic value in some horses at some stage of worm infection. However, it must be noted that some worms cause constipation for short periods in some horses.

- Abnormal appetites. Horses may eat articles such as paper, matted hair, bark of trees and gnaw on wooden articles such as posts, trees, neck yokes and leather trappings. Sometimes this condition can be traced to mineral deficiencies, internal parasites or lack of total nutrients. Mineral and vitamin deficiencies could act with worm parasites to the disadvantage of the horse.

- "Potbellied" condition. Ascarid worms, with or without the presence of stronglid worms, frequently cause abnormally large abdominal girth, some muscle weakness and poor growth, especially in the case of colts.

While symptoms are helpful in diagnosing worm problems in horses, perhaps the better way to determine kinds of worms is to have a reliable laboratory or a local veterinarian make fecal analyses.

Prevention

Sanitation and management practices should be used to assist in controlling internal parasite infections. Remember that foals are born free of internal parasites, they get them from direct or indirect contact with older animals that are carrying the infections. All of the worm parasites discussed here use feces or manure as the means of spreading the infections by contamination of feed and water supplies or the environment.

Transfer stages of these worm parasites do not actively seek the host to complete the infection process. Instead, they rely on chance to be picked up and swallowed. Thus only a very small percentage actually complete this hazardous step in the life cycle. To compensate for this, large numbers of eggs are produced by the female worms to start the transfer process.

Sanitation and management practices aid in controlling or minimizing spread of the infections. These practices assist the natural destructive forces such as sunlight and drying during the transfer stages. Also, susceptible animals should have limited contact with contaminated pastures, paddocks, or stables.

Treatment

In addition to the sanitation and management practices above, treating animals with specific drugs, commonly referred to as antihelminthics, is generally necessary to get effective control. These drugs remove the parasites from the intestinal tract. Thus the treated animal is relieved of the immediate damage or injury caused by parasites. But probably more important is removing the parasites which breaks the cycle. This serves to reduce contamination of the environment with transfer stages thereby limiting the spread of the infections and protecting animals from reinfection. In most cases, your veterinarian should administer antihelminthics. Follow his counsel and advice on a parasite control program.

A number of new drugs have been developed in recent years. Some are effective against all four of the important kinds of parasites and thus are referred to as "broad–spectrum"; in action. Others are most effective against one or two of the kinds of parasites and these are known as "specific" antihelminthics. A more recent drug has been developed that is injectable and is effective on all classes of parasites both in the digestive tract and migratory stage.

Most drugs are best administered by stomach tube, a procedure requiring a veterinarian’s knowledge and skill to obtain most effective action. Some of these drugs, and others, can be given by mixing the proper dose in the grain ration. When the feed method is used, give special attention to see that the medicated grain is consumed by the animal if you expect results.